Policing in Schools

On June 2, 2020, Minneapolis Public Schools terminated its contract with the Minneapolis Police Department for the services of school resource officers. The board unanimously voted in support of the resolution, which stated “any continuing contract for services with the Minneapolis Police Department [does] not align with the priorities of the District’s equity and social emotional learning goals.” By the end of summer, MPS Superintendent Ed Graff will need to prepare and submit recommendations to the school board on how the students of MPS will be served and safety maintained without the presence of Minneapolis PD in school buildings.

Over the past few decades, partnerships between local educational agencies and police departments have become more prevalent. In 1975, only 1 % of U.S. schools reported having police stationed on campus. By 2014, 24% of elementary schools and 42% of secondary schools reported having sworn law enforcement on campus. Approximately 77% of public schools with enrollment of 1,000 or more students employ a school resource officer (“SRO”). 79% of these officers carry a firearm while on duty in school buildings.

A school resource officer or “SRO” is defined by federal law as a “career law enforcement officer” employed by a police department and assigned with “sworn authority” to a local educational agency. The school resource officer’s codified role is to: (a) educate students; (b) develop or expand community justice initiative for students; and (c) train students in conflict resolution, restorative justice, and crime and illegal drug use awareness.

SROs, however, often act outside the scope of this legally defined role by exercising their authority as a law enforcement officer to execute arrests. The growth of SROs in schools is correlated with an increased rate of school-based arrests. Instead of receiving school-based discipline for behavioral infractions, in greater numbers children are being arrested for minor offenses, such as disorderly conduct or simple assault, directly contributing to the “school-to-prison pipeline.” Pennsylvania has the third highest student arrest rate in the country, with a 24% increase in school-based arrests between 2013-2014 and 2015-2016.

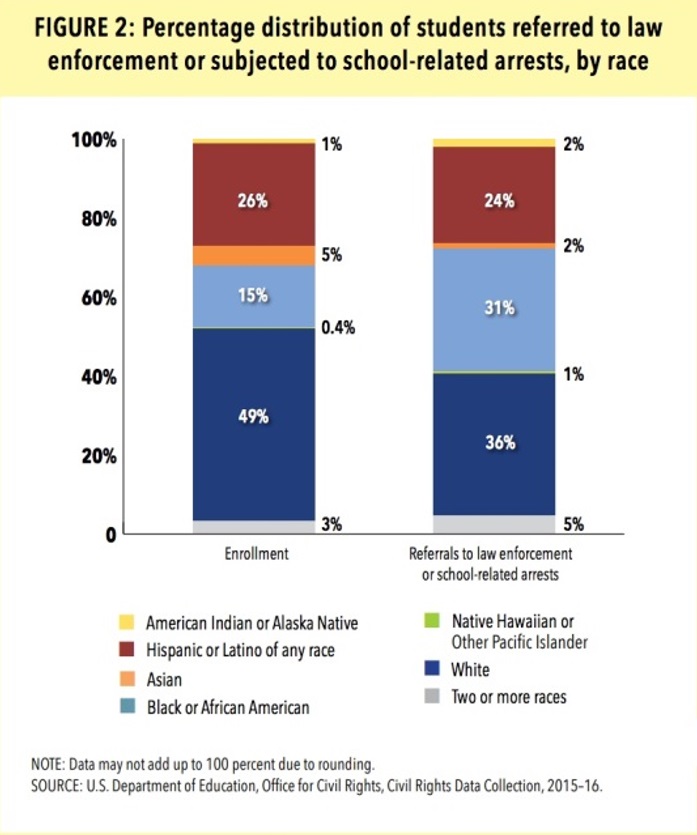

Children who are black/indigenous people of color (“BIPOC) are disproportionately impacted by school-based policing. Although black students represent only 15% of all U.S. students, they account for 31% of school- related law enforcement referrals or arrests. Overall, black boys with disabilities are 29.9 times more likely to be arrested than white boys without disabilities. Black girls are 4 times more likely in the U.S. and 5 times more likely in Pennsylvania to be arrested in school than white girls.

Racial disparities in school discipline are widespread and persistent “regardless of the type of disciplinary action, level of school poverty, or type of public school attended.” These disparities are not explained by more frequent or more serious misbehavior.

In 2014, the U.S. Departments of Education and Justice issued guidance to schools for adopting policies and practices that reduce racially-biased administration of discipline; however, this guidance was rescinded by the Trump administration in 2018.

There is little to no data to support that increased police presence in schools leads to safer school environments. Instead, evidence shows that school-based police officers have resulted in the unnecessary criminalization of children, particularly BIPOC children, with irreversible consequences.

As communities everywhere reevaluate the roles and responsibilities of local law enforcement officers, school districts have the power to renegotiate its contracts with local police departments and to redistribute funding.

Communities can review the current contracts imbuing SROs with the authority to police in schools. By law, all Pennsylvania school districts are required to negotiate Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) with area law enforcement. The Pennsylvania Board of Education has approved a Pennsylvania model MOU, and many districts adopt that model with only minor modifications.

School districts are free, however, to add provisions to their MOUs with local law enforcement, as long as they do not conflict with state or federal law.

For example, the MOU between the Philadelphia School District and Philadelphia Police Department prohibits SROs from arresting children 10 and under. In some non-Pennsylvania districts, MOUs include protections for students’ rights (such as limitations on student searches), limits on arrests at school for non-school-related matters, and parent notification requirements. MOUs might also include training requirements, including training for responding to incidents involving students with disabilities.

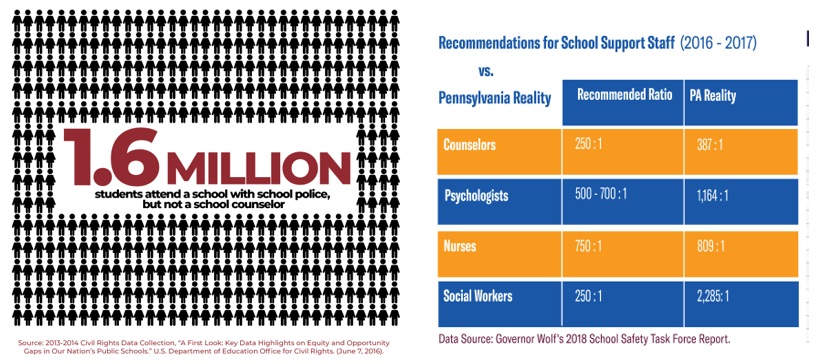

“Every dollar spent on police, metal detectors and surveillance cameras is a dollar that could instead be invested in teachers, guidance counselors, and health professionals that support, not criminalize children.” – https://advancementproject.org/wp-content/uploads/WCTLweb/docs/We-Came-to-Learn-9-13-18.pdf?reload=1536822360635

Communities can also advocate for a reallocation of resources in municipal and school budgets.

In June 2018, Pennsylvania legislators enacted Act 44, which allocated $60 million in grant funding for the purpose of increasing school safety. Largely, these grants have been used to fund police, equipment, and training. This funding is in addition to a state grant program, begun in 2010, which funds school police positions through the Pennsylvania Department of Education’s Office for Safe Schools.

Instead of devoting funds to school policing and law enforcement, school districts could divert resources to evidence-based practices and programs that research has shown leads to safer school climates, such as restorative justice programs, holistic community supports for students and families, and additional support staff. In particular, school districts could hire additional counselors, social workers, and behavior interventionalists. These funds could even be used to support smaller class sizes, which is also a contributing factor to school safety.

Minneapolis Public School’s board of education has shown that school districts have the power to autonomously disrupt the paradigm of policing children in school and look for alternative solutions to secure school safety and improve the school climate.

If your child or a student you know has been negatively impacted by police presence in school, please give us a call at 610-648-9300.